She Was Not Mad

How the 19th-century American asylum was used as a tool to control and punish women

In the winter of 1896, a man named George Brower received an anonymous letter at his farm in Keyport, New Jersey. “Stop abusing your wife and take her from the asylum,” it read. “If you do not, tar and feathers await you some dark night.” The letter was signed “The Lady White Caps.” The first letter was followed by a second, signed the same way: “Leave town at once. It is useless to defy us. Your house will be burned and your new horses will be taken away.”

Publicly, George claimed to be unbothered by the threats. “Let ‘em come. I’m ready for the white caps,” he told The Bridgewater Courier-News. “There are a lot of busybody women here who are prompted by malice to talk through their noses.” But he bought a pound of buckshot and a pound of powder and began sleeping with a loaded shotgun beside his bed.

George’s trouble started in January of that year, when he tricked his wife Anna into a carriage bound for the insane ward of a hospital in Trenton. Anna was committed against her will and held while doctors examined her; her husband had pre-paid for thirteen weeks’ board. She wrote letters to friends telling them that she was being kept in the asylum not because of her mental health, but because her husband wanted to take property from her, which he’d tried to do in the carriage ride to the hospital. “My husband told me he had me in a place that I would not get out of until I signed over the mortgage to him,” Anna told a reporter for the New York Herald. Anna refused to sign over the property to her husband and instead placed the mortgage papers in the care of the doctor in charge of the hospital.

A month into his wife’s confinement, George Brower was informed by the hospital that Anna would have to be released back to him because she was not suffering from any mental illness. He appeared at the hospital grounds and then frightened her with descriptions of “what he would do” when he got her back to Keyport. She managed to escape from him and from the hospital, and took refuge with friends in Brooklyn. In her own words in the Keyport Weekly, Anna wrote about George’s “inhuman, cowardly brutality,” and the years of abuse she had suffered at his hands, “ill-treatment to an intensity pen and ink cannot describe,” even before he forced her into the hospital. She said he had threatened to have her “railroaded to a lunatic asylum” many times. “She Was Not Mad,” the Herald’s coverage proclaimed after her escape, noting that the stress of Anna’s confinement had streaked her hair with gray.

George’s attempt to use the asylum to control his wife was not an uncommon scheme in this era; for the unscrupulous husband, the asylum was a ready ultimatum that could tame unwanted behavior and silence dissent; it could clear the path to a new marriage to a younger woman; it could provide an opportunity to secure sole custody of shared children; and it could act as a means to seize a spouse’s property.

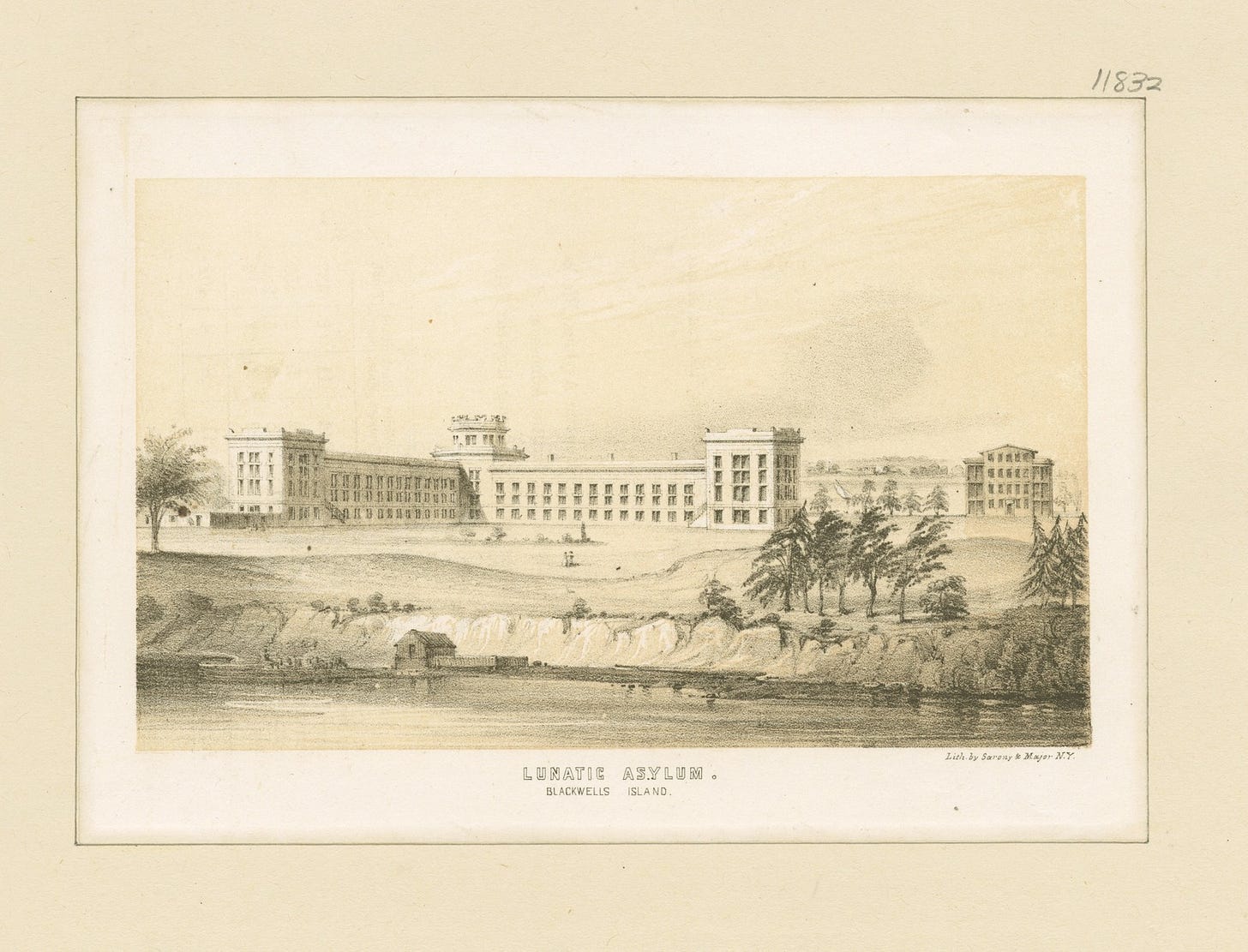

In the late 19th and early 20th century, the American papers were full of stories about women imprisoned in asylums, just like Anna Brower was at Trenton. In New York, there was Gesina Satow, whose abusive, alcoholic husband had her sent to Blackwell’s Island because he knew she had consulted a lawyer about attaining a separation from him; she subsequently had to fight for custody of her children. There was Eunice Kuster, who was arrested in the street and taken to Bellevue, and who said her husband had not only tried to have her committed multiple times but had also conspired to poison her. There was Sarah Zeff and Julia Egan and Jennie Shackman and Harriet Beach, wife of the editor of Scientific American, who was committed to Bloomingdale Asylum because she believed in ghosts.

And then there was Mrs. Haubert, who was ambushed on a crowded Long Island railroad platform and dragged to an asylum in Amityville in 1893. Just as the train whistle sounded, her husband snatched her four-month-old baby from her arms, and three guards restrained and then carried her, struggling, to a waiting wagon. She fought so hard that at one point they dropped her, while onlookers watched in horror. “Give me my child! Give her back to me!” she screamed at her husband. “I’m not crazy, but you’ll drive me so!”

When Mrs. Haubert’s father visited her in the asylum, he declared her confinement an “outrage” and called her his “poor, abused daughter.” And then he told the staff that she would be staying. “Doctor, she is not insane,” he said. “But she shall remain here, where she will be better off than with that husband of hers.”

Once committed, people had little recourse. To be legally locked away, you didn’t need to be deemed a danger to yourself or to others, and your ability to protest, especially as a married woman, was almost nonexistent. Patients had no say in their own treatment and were sometimes not even told what their diagnosis was. They were at the mercy of the asylum’s medical staff unless they were able to reach and convince sympathetic friends or family to help, and patients’ mail was often censored and surveilled, or completely cut off. An item in the Brooklyn Times Union in 1903 described a bottle that had washed up on the beach at Fort Hamilton containing a message from a woman trapped in an infamous city asylum:

I was sent here by Judge Hogan on April 6, 1895. He said I was insane. God help me! We are not wanted by any one once we are on Ward’s Island. They strip us and drive us in a pond like so many sheep until we are nearly dead. Please take this letter and rescue me.

The letter included addresses for her family members, who, when contacted, said that she was “hopelessly insane.”

The most famous story of a woman confined to a mental institution by a nefarious spouse is probably that of Elizabeth Packard, who was, in her own words, “imprisoned in Jacksonville Insane Asylum,” and “placed there by her husband for THINKING.” She had made the mistake of publicly disagreeing with her minister-husband about theology. One of her doctors later concluded that she was insane in part because “her hatred of her husband had something diabolical about it.”

After three years in Jacksonville, Packard secured her release and became a reformer and activist, campaigning not only for the rights of married women, but for the rights of all committed patients, because she had witnessed firsthand the terrible abuse inflicted on the mentally ill in asylums. In a letter to the supervising physician at the asylum, Elizabeth Packard promised to expose all she had endured and seen there: “I will not suffer humanity to be so abused as you do here without lifting my voice against it—and I will be heard!” Elizabeth Packard would be heard, and heard by many people; she wrote and published a number of books about her experiences, and they sold well enough to “provide her with a comfortable income” in addition to working to persuade political leaders and legislators to take up her causes.

You can hear an echo of Elizabeth Packard’s plaintive declaration—“I will be heard!”—in Britney Spears’ statement to a California court last week, in which she detailed how the conservatorship put in place with her father at the helm 13 years ago was both controlling and abusive, denying her right to determine her own medical care or to make reproductive decisions about her own body, even as everyone around her profited from the money she earned as a pop star. “I want to feel heard,” Spears said, adding that her dad and her management team “should be in jail.” “I want to be able to be heard on what they did to me by making me keep this in for so long,” she said. Like Packard, Spears knew that to change her circumstances, she needed to reach the press and the public—the outside world, which has judged her private life from afar for more than 20 years.

A recent article in TIME Magazine estimated that there are currently 1.3 million Americans held under conserveratorships like Spears’, and most of these arrangements exist with “little oversight,” and can “strip people of their basic civil rights.” Advocates for disability rights quoted in the article are hopeful that Spears’ story will bring attention to people suffering in conservatorships who don’t have access to the platform that she does.

In the published account of her ordeal, Anna Brower wrote about her reluctance to air her “domestic affairs” in the newspaper. But she felt she had to “break the silence” she had held for 15 years, to show her friends and the public “the true state of affairs” about her husband’s treatment of her. She wrote that she had kept herself “secluded” in Keyport because of her husband’s “disposition,” and she had been surprised by how many people were supportive of her now. “I never thought that I had such a number of friends,” she wrote. “And I thank you all for the friendship shown.” She also thanked the Lady White Caps for their help, though she “earnestly beseeched” them not to carry out their threats “unlawfully.” “If legal means cannot punish him,” she wrote, “I must leave the judgment in the hands of Him who said, ‘Vengeance is mine.’”

That vengeance came for George Brower sooner than Anna might have expected. He died, at 53 years old, just one year later, leaving Anna, for once, in full possession of both her property and person.