The Poor Unfortunate Murdered Girl

Mary Rogers' death in 1841 inspired frantic media speculation, criminal legislation, and Edgar Allan Poe's fiction

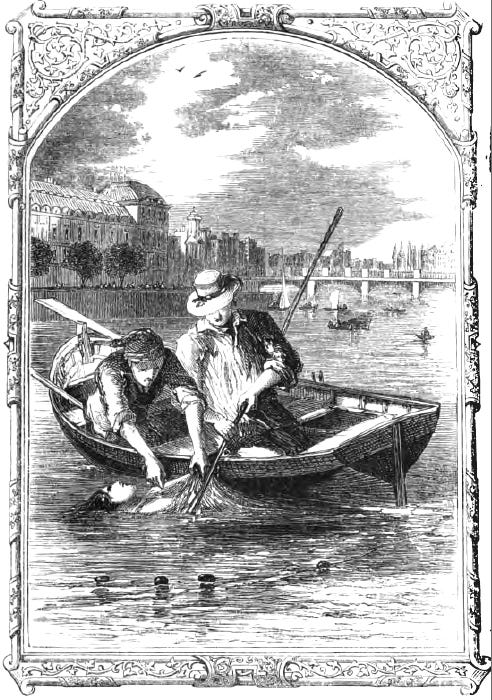

In the late summer of 1841, the New York Weekly Herald published a lengthy description of the body of a young woman. The article is a careful inventory of a floating corpse: it tells of the girl’s “light gloves” and her “watery fingers,” the bonnet still on her head and shoes still on her feet, her “battered and butchered” features “scarcely visible” because “so much violence had been done to them.” The writer takes great care to set the scene where the body was found in the river; on a peaceful stroll along the Hudson in Hoboken, readers are invited to picture a “beautiful walk” past “deep green trees” and “marble cliffs,” all lit by “the last beams of day,” which cast the water in a rosy tint.

The writer is not alone in gazing at—and recoiling from—this “horrible spectacle.” The paper reports that “the crowds flocking to Hoboken have been immense, and the legends circulated have been innumerable,” noting the behavior of these curious visitors to the site “of the deed”: “groups would stop a while, stoop over the remains…and pass along.” There is also a “rude youth,” who grabs the dead woman’s leg, and makes “unfeeling remarks.”

Crowds were flocking to Hoboken in part because of the Herald’s own efforts to publicize and sensationalize the body’s discovery, autopsy, and identification as Mary Rogers, a cigar store employee, about twenty years of age, who worked on Liberty Street in Manhattan, and whose beauty was said to be a draw for the shop’s male clientele. Rogers was first reported missing by her distressed fiancé, Daniel Payne, in a notice in the Sun. When she failed to return to the boardinghouse where she lived with her mother after leaving for a Sunday visit to her aunt’s home, he traversed the length of the city in search of her, trekking from Harlem to Williamsburg to Staten Island before giving up, despondent.

The penny press of the 1840s feasted on the details of Mary’s death, printing nearly every line of the lurid coroner’s report and picking over the minutiae of witness accounts, suspect speculation, and wild allegations for weeks after news of the case first surfaced. The press was full of baseless theories and breathless questions: Was Mary murdered by a gang of ruffians? By a swarthy, unscrupulous sailor? Was it suicide brought on by destitution and poor marriage prospects? When Mary’s suitor Daniel died near the site where her body was discovered with a miserable note and a bottle of laudanum at his side, the coverage only became more fevered.

In the uncorroborated pages of the tabloids and later on in fictionalized accounts of the story like Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” Mary-the-real-person was erased and replaced with other Marys, each one a cipher, a stand-in for fears about women, work, sexuality, urban crime, and gender roles. She could be a virginal, perfect maiden, the defenseless victim of a terrible act, her demise turned into a rallying cry for reformers against a teeming city beset by rampant violence. She was an unsolvable puzzle, a parlor game wherein the circumstances of her disappearance and death were subjected to paragraphs and paragraphs of conjecture and hypotheticals. Or she might be an amoral vixen, who cavorted with men in public and then suffered the consequences.

Mary Rogers’ case was never formally resolved, but not long after her body was found, another explanation for her death appeared in the papers. She was not a victim of murder at all, but of “the infernal practices to procure abortion, for which our city has for some years been notorious,” in the words of Horace Greeley, writing as a correspondent for the Madisonian in August 1841. At first, public opinion stood against Greeley’s theory, because it was viewed as an attack on the dead girl’s honor. “We do not envy the man’s heart who could write this most foul calumny on the character of the poor unfortunate, murdered girl,” was the Herald’s response.

In 1842, a witness, Fredericka Loss, came forward on her own deathbed, claiming that the man in whose company Mary supposedly spent her last hours was a physician whose botched procedure led to Mary’s death. After relating the facts of Mrs. Loss’ confession, the New York Tribune expressed gratitude that “the terrible mystery” which struck “fear and terror to so many hearts,” was “at last explained” by “circumstances in which no one can fail to perceive a Providential agency.” The paper went on:

We rejoice most deeply at this revelation, and that the scene of the unhappy victim’s death is relieved of some of the horrors with which conjecture, apparently well-founded, had surrounded it.

In revised versions of “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” Poe included hints at abortion as the solution to the case; Mary’s story became linked with Madame Restell, the infamous abortionist of Fifth Avenue; and in 1845, New York state passed a statute that made it possible to prosecute women who sought or obtained an abortion, setting out fines and prison sentences as punishments. The law mentioned Mary Rogers as “one of its justifications.”

It didn’t seem to matter that the original coroner’s report recorded the cause of death as strangulation, pointing to bruises on Mary’s neck and a length of lace tied so tightly under her chin that the coroner at first didn’t notice it, or that Mary’s body bore evidence of struggle and sexual assault. Nor did it matter that, under this new law, made in her name, if “poor, unfortunate” Mary had survived an abortion, she could have been jailed.

In the same year, New York also passed a Police Reform Act, which “professionalized” and “modernized” the police department, and “codified surveillance as an aspect of public policy,” according to Amy Gilman Srebnick’s book about Mary Rogers, The Mysterious Death of Mary Rogers. Though Rogers’ case and the moral outrage it inspired was one of many factors behind the passing of this law, Srebnick writes about how Rogers’ murder “was a particularly useful device in fostering hysteria over crime and social disorder” at the time, a device that would-be police reformers used.

In the introduction of her book, Srebnick writes about her feeling of unease as she confronted the utter absence of Mary Rogers’ personhood in the historical record. “Figured in everybody’s image but her own, Rogers remained a woman without a family, without a past—without an identity,” she writes, of her research. “From the moment of her disappearance, attention had been focused on her gruesome death and the men most likely responsible for it…I found myself increasingly uncomfortable with the degree to which Mary had become so completely a cultural construction, defined by her sexuality and her apparently violent death.”

You can hear an echo of Srebnick’s dismay in Moira Donegan’s recent tweets about Gabby Petito, the 22-year-old who disappeared on a road trip with her boyfriend this summer and whose remains were found in Wyoming this week. Donegan describes the “jarring” transformation of tragedy into “entertainment in real time,” and about “the way the death of a woman is merely the opening scene of a drama that’s really all about the motivations, attempts at impunity, and ultimate fate of her male lover-abuser-killer, whom the audience is supposed to treat as the story’s most worthy mystery.”

Plenty of worthier “mysteries” abound, other questions about our collective 180-year-old failure to evolve beyond the voyeuristic, charged allure of turning a real person’s death into a “true crime” narrative, about the contrast between the intense, national clamor over the blonde Petito’s whereabouts and the silence that cocoons the fates of thousands of indigenous and Black women and girls who go missing every year, about why so many of the people who are publicly enraged by cases like Petito’s are also capable of tolerating, ignoring, and justifying gendered violence and harassment in other circumstances.

In The Mysterious Death of Mary Rogers, Srebnick acknowledges the limits of the archives; despite painstaking genealogical work and diligent reconstruction of the social, economic, and political world that Mary inhabited, it is still hard to make out the specific contours of her identity. If you squint, though, it’s possible to imagine Mary Rogers, out on a summer Sunday afternoon in the city, wearing a white dress, twirling her parasol, tying her blue scarf, fixing her hair, leaving roses in her suitors’ keyholes, writing sweet-nothing messages, smiling at shop customers. Maybe it’s still possible to see her not as a symbol of anything but herself, as a singular, ordinary young woman who glimpsed and grasped for a new kind of female freedom—and who was punished for it.■